By Nargess Banks

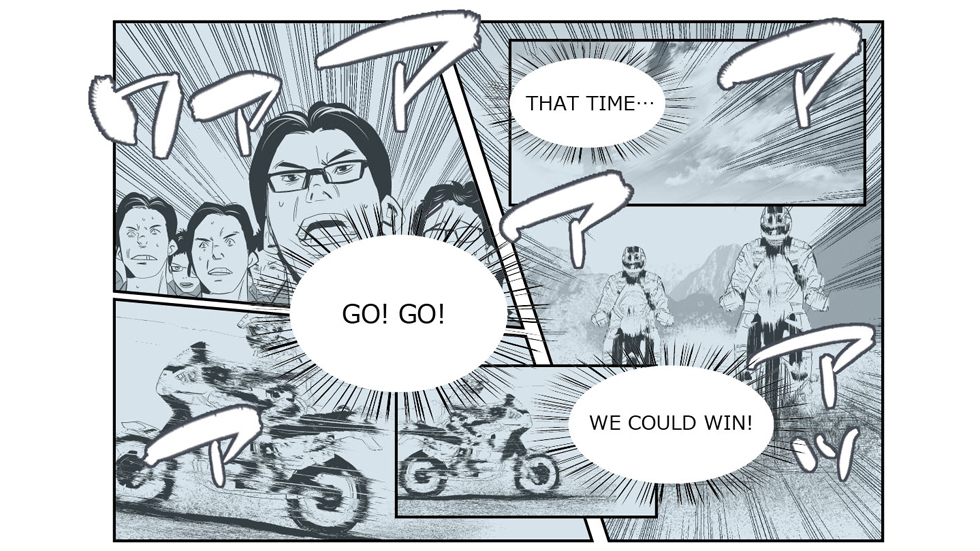

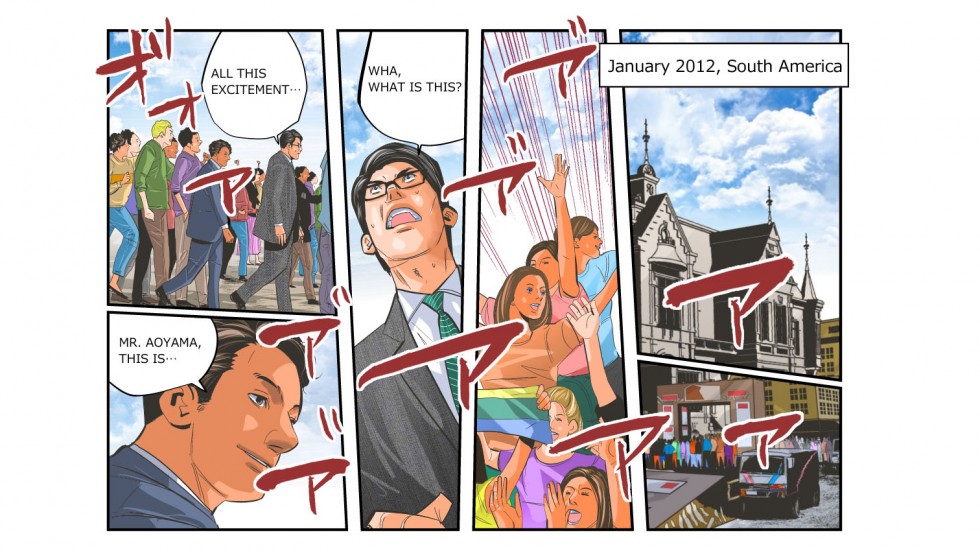

To celebrate its return to the legendary Dakar Rally with TEAM HRC, Honda has released a series of manga novels written by the rally team and illustrated by artist Keiichiro Okamoto.

A tale of adventure and endurance

Manga and its animated sibling, anime, are deeply entwined with Japanese culture. Manga is a comic art form born during Japan’s World War Two occupation which draws on the influence of US comic books. Enjoyed by all ages and social groups in Japan, its wide appeal, plus its often heroic and exciting subject matter, lent itself perfectly to Honda’s Dakar Rally story.

The Dakar Rally – an ultimate endurance race

The Dakar Rally is perhaps the toughest race on Earth. It was devised by Thierry Sabine in 1977 after an epiphany while lost on his motorbike in the Libyan desert during the Abidjan-Nice Rally. You or I might find the very thought of this situation terrifying, but Sabine – ever the racer – decided to share his incredible adventure with other enthusiasts.

He designed a route that started in France, continued to Morocco and crossed Niger before eventually finishing in Dakar in Senegal. Incredibly, he found plenty of willing competitors to take on the challenge.

The Paris-Dakar Rally established itself quickly and has been a magnet to world’s best riders and drivers ever since. Hundreds participate every year on motorcycles, ATVs, and in specially prepared cars and trucks. The original route through Africa was abandoned in 2008 after political unrest and concerns over safety, so now it winds its way through South America instead, taking in Argentina and Bolivia before coming to an end some 8,000 km later in Chile.

Honda’s TEAM HRC rider Paulo Goncalves competing in the 2014 Sealine Cross in Qatar

Honda goes manga at the Dakar Rally

Honda has always embraced the most exciting challenges and won the motorcycle class of the Dakar from 1986 to 1989 consecutively. In 2014 they returned to the race with Team HRC after a 24 year absence, winning 6 of the 13 stages and scoring a 5th place finish.

The story of this return has been turned into a series of manga-style comics called Road to Dakar. Rather than a straightforward tale of the race, Road to Dakar delves into the engineering process, the highs and lows of testing and developing the machines, and the stories of the riders and the engineers, told in this inventive Japanese visual style.

TEAM HRC and Honda will be back and looking for victory when the 37th edition of the legendary off-road race starts on 4 January 2015. The team, competing on new factory-spec rally versions of the Honda CRF450, will include Helder Rodrigues and Paulo Goncalves of Portugal, the UK’s Sam Sunderland, Argentinian Javier Pizzolito, and Joan Barreda of Spain. The road to Dakar and the challenge continues…

The story of manga

Manga is a cultural phenomena in Japan with tentacles reaching into every part of society. Taking readers into a highly imaginative and often stylised world, manga stories cater for all and cover many genres – from action to romance, sci-fi, fantasy, fiction and horror. There is even a manga style for business and commerce!

Manga is big business in Japan. Since the 1950s it has formed a significant part of the publishing industry, not only domestically but also in Europe and the US where these cult comic books enjoy a loyal following.

There’s much debate as to its origin, but the term ‘manga’, which roughly translates to ‘cartoons’ or ‘playful sketches’, dates back to the 19th century. It was reputedly coined by a wood pictures artist named Katsushika Hokusai who wanted to describe his sketches. The drawings have a long and complex history rooted in classical Japanese art that dates back as far back as the 12th century – though it’s hard to detect much of this connection in modern manga.

Instead, much of what we see today is a fusion of East and West – a by-product of the post war years between 1945 and 1952 when Japan was under US occupation. The American GIs brought with them comics from home and introduced Hollywood films and Disney cartoons that significantly influenced manga’s style and storytelling.

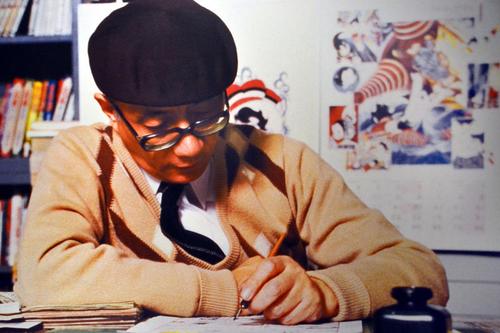

Two manga artists, or mangaka, working in this period are considered to be the pioneers of modern manga. Osamu Tezuka and Machiko Hasegawa lead the scene with their very distinctive styles, establishing the main manga genres that were adopted by later artists.

Tezuka created the now-classic Astro Boy in 1952. It later became the first manga to be adapted for animation. With his highly cinematic style – where rapid close-ups and distant drawings create a sense of movement – and big adventure stories, Tezuka is widely regarded as the father of shonen manga.

Hasegawa, on the other hand, focused on more realistic narratives: tales of daily life with leading female characters animated in a much more simple style that was labelled shojo manga. Her most recognised comic, Sazae-san, was later made into a popular Japanese anime television series.

Modern manga

Manga today fuses Eastern and Western comic styles with Japanese storytelling that can often include moralistic tales of honour, pride, respect and humility. They can also be adventurous, imaginative and at times pretty violent and racy – although always unmistakably Japanese.

Shonen and shojo remain the more dominant genres – the former delivering adventurous boyish themes, the latter light-hearted storylines and, often, romance. Other manga styles also exist such as kodomomuke for young kids, and the more adult themed seinen and josei.

The influence of manga can be seen everywhere in Japan. You need only to turn on the TV to witness how closely it forms the vocabulary for popular culture, be it the endless broadcast of animations, or the bold colours and visual format of chat shows.

Even higher forms of art take inspiration from manga. The country’s most celebrated contemporary export, Takashi Murakami, whose works are sold for millions worldwide, is proudly influenced by the genre. His distinctive superflat style marries traditional Japanese painting and classical subject matter with contemporary manga culture.